How do you know when it’s time to bring the curtain down on your characters? I got to thinking about this after hearing Kevin McGill of the sadly defunct podcast Guys Can Read lamenting what a damp squib the Smallville finale turned out to be.

I haven’t seen many episodes of Smallville, but after ten seasons there are only two places a show can end up. Two different kinds of whimper that can supplant the bang of a timely end. One is when the show runs out of steam. You keep tuning in because you care about those characters, but you know they’re not going to be hitting balls out of the park ever again. Case in point: the final season of Babylon 5. That wasn’t Mr Straczynski’s fault, but it was still an exhausted winding down, best forgotten, of what had been at times the most exciting SF show on television.

Or the show can spiral into the sucking singularity that is narrowcasting. I’m a devoted Buffy fan, but I’m not sure that anyone could pick it up at the start of season seven and have any idea what was going on. I got my first whiff of the narrowcasting bouquet when Doctor Who fan discussions raged about whether or not Rory is still an Auton. And if that means nothing to you – okay, you got it; that’s narrowcasting. (Well, also it’s an example from back in the Matt Smith era, which is the last time I watched the show, but there are plenty of present-day examples — probably from Who itself, come to that.)

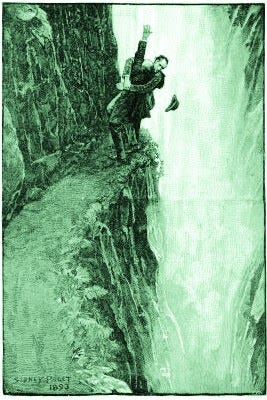

Stories have an end, even when they’re about characters we really love. You may not want to admit it, but your parents’ story ends when you leave home. After that it’s all reunion shows – usually “The One with the Cranberry Sauce”. And endless reunion shows are fine for real people whom you love, but in the case of fictional characters then it really is time to boot them off Reichenbach Falls.

The Norse gods had Ragnarok. The British Empire had World War Two. Beowulf had his dragon. The end dignifies what came before, and sometimes redeems it. Stories need endings. At the close of a well-crafted tale you should be sad to leave the characters – even the bad ‘uns – but you know it’s right. Their story is over. “I feel… cold,” says Captain Barbossa, and it’s such a brilliant culmination of everything that’s gone before that it ought to be the end. Only the magical might of Calypso and the million-dollar demands of Disney could undo so absolutely essential a demise.

Ongoing comic book sagas risk the calamity of too long a life more than most. Sandman is great because it built to a definite conclusion. If we properly cherish what we were given in Alan Moore’s original Watchmen, we won't ask to read the ongoing adventures of Nite Owl and Silk Spectre. Conversely, at a full century of issues, even the freshness of 100 Bullets was starting to feel more than a little stretched out. Knowing when to take a last bow is the mark of an effective performer.

Once the characters’ story is told, gentle breath of yours must fill their sails — Shakespeare thereby acknowledging, as he threw aside his pen for good, that ultimately all great stories are merely enablers for the reader’s own imagination.

I yearn for the days of short, self-contained, one-off stories: 150-200 pages, tops, something you can read in an evening. No sequels, no spin-offs, no ongoing series, just a damn good yarn, and then you move on to something else. Sadly, although that makes for great entertainment, it's not good business for publishers, because readers are usually more invested in the IP than the author.