Ineffective altruism

What are our responsibilities to future generations, and does it help to be logical about it?

If you’re familiar with the effective altruism movement, chances are your opinion of it has been overshadowed in recent years by the example of bad actors like Sam Bankman-Fried. There’s no shortage of podcasts and articles about Bankman-Fried’s downfall; if you want to refresh your memory, I recommend this episode of Tim Harford’s Cautionary Tales.

Effective altruism appealed to me from the moment I first heard about it. As a child I could never see the point of all the separate charities. What if mere marketing meant that guide dogs for the blind ended up with ten times more than they could ever spend while Estonian orphans went hungry because Romanian orphans were on the front pages? I thought all charity donations should go into a single fund that would be allocated according to need and effectiveness.

Ah, but who’d decide? Fair question. We could agree a system for calculating how to share funds out (much like GoodWell’s analysis) but we’d argue about how much should go to animals and how much to humans, and how much to humans today compared to humans in the future. The young Morris was by inclination a benevolent dictator, so swept such questions aside.

I must also be a natural longtermist, as I’ve always given money to cancer research rather than palliative care. Making one person more comfortable now rather than going straight for the heart of the problem makes no sense to me. Again, you may not agree. Statistically you almost certainly won’t. I’m just mentioning this in the preamble to give context to the rest of the discussion.

Hold and rewind. I mentioned longtermism, but there seems to be lack of clarity about what that means. It’s often said that Sam Bankman-Fried was “too rational” and that his example has discredited longtermism and effective altruism. This strikes me as like saying that Jimmy Swaggart was “too devout” and that his example has discredited Jesus’s teaching. First of all, let’s look at the concept of earn-to-give. Is that rational? We have to consider how the money is being earned. It is quite likely that many of the jobs that earn one person tens of millions of dollars a year are causing harm to others – maybe more harm than can ever be redressed by giving that money away. Will MacAskill himself is on solid ground; his academic’s income is damaging no one. But Sam Bankman-Fried started on ETFs and moved on to crypto, both careers unlikely to be wholly victimless.

Then there’s the questionable logic behind extreme longshots. Tim Harford’s podcast, for example, recounts how Bankman-Fried spent millions on Carrick Flynn’s political campaign. The argument is that it makes more sense to aim for a one-in-a-million chance of getting somebody elected who will plan for future pandemics than spending money on bed nets to save a few lives right now. As a self-confessed longtermist I should be on board with that, surely? No, because history is chaotic. There are too many unpredictable steps between throwing money into political ads for one politician and having an effective pandemic policy ten or twenty years later. It could have the opposite effect, whereas in the case of the bed nets I can estimate pretty precisely how many lives my dollars will save.

That’s not a case of Bankman-Fried being too rational. It’s an example of the sort of thing that reckless people do when they are too impatient to solve problems methodically. In fact, given such behaviour we can see it’s no surprise how Bankman-Fried ended up.

If Sam Bankman-Fried had really been “hyper-rational” he’d still be free and making money and maybe even doing some good with it. It was the risk-taking aspect of his personality that scuppered him. Even if he had behaved logically, which I dispute, the argument that too much logic can lead to inhumanly unethical conclusions is nonsense. If your logic leads you to genocide or tyranny or callousness, it’s not the logic that’s at fault so much as the premises. Crime and war sometimes follow logically from the axioms and goals you start with. Not Sam Bankman-Fried’s crimes, though. Those weren’t characterized by logic, just by arrogance, intellectual laziness, and ineptitude.

But let’s not spend too much time on Bankman-Fried. The point is to discuss longtermism. One criticism of the idea is that we cannot give equal weight to the person on the other side of the world (in Singer’s drowning child thought experiment) or in the distant future because we will always prioritize our own family and friendship group. But hang on – our entire system of justice and government is designed to correct for biases like that. We deplore nepotism and favouritism. We don’t ask victims or their families to pick punishments for criminals. Nobody asks for a clarification of the Trolley Problem: “Are any of the people on the tracks related to me?”

I say this without naivety. Many people would like to give the plum jobs to their family members. People who get into power frequently exploit it to enrich their cronies and appoint their relatives to key positions. The other day I told a friend about my personal whimsy of having a company devoted to developing Von Neumann probes, and he said, “But why? You’d never live to see what happened to them.” To my friend, as to many others, if something is going to have an effect beyond the lifetime of his grandchildren, he doesn’t care about it.

The point is, we know about all those human foibles – short-term thinking, nepotism, and so on – and we build social structures to correct for them. We mostly agree that logic will stand us in better stead than our emotions. (And by the way, if you can’t grok my example of Von Neumann probes, just substitute pandemic planning or vaccine programs or fusion research – all worthy projects where the person who starts it may not live to see the outcome.)

A lot of longtermists say we should aim to maximize human happiness, and if you apply the clockwork logic of a 1960s sci-fi computer to that you may end up concluding we need to ensure a population of trillions. A more sensible conclusion is that we should try to improve disinterested justice for all, though I’m not sure equality would make humans happy. Many of them care more about being richer than their neighbour – or of higher status, more to the point – than whether everyone is getting a fair share. If they could mentally compare themselves to a neighbour living two hundred years ago they’d be wildly content, but that would invite also resentful feelings towards the neighbour two hundred years in the future, who may actually be scrabbling for grubs in a baking wilderness but who we imagine enjoying post-scarcity and a long, disease-free life.

Personally I’m not so bothered about happiness. I think more about our duty, as possibly the only technological civilization in the galaxy, not to go extinct without leaving something to replace us. Unfortunately for my aspirations, and for all the philosophers like Aristotle, Kant and Confucius who constructed a concept of eudaimonia based on responsibilities and justice, the evidence suggests we are not a very dutiful species and we have almost no ability to think beyond the immediate future. Perhaps my donations to cancer research will go to waste, Earth becoming either a nuclear desert or a runaway greenhouse hell.

We need long-term thinking to solve humanity's biggest challenges, yet we're evolutionarily wired for short-term bias. We’re not going to be helped to transcend these limitations by a retreat from rationalism as being “not human enough”. Instead we need to design a more nuanced model, one that combines long-term vision with methodical, measurable steps. Truly effective altruism would involve (among other things) rigorous cause-and-effect analysis, a realistic assessment of the limits of our predictive abilities, and perhaps a portfolio approach that balances sure wins (bed nets) with carefully chosen long-term bets.

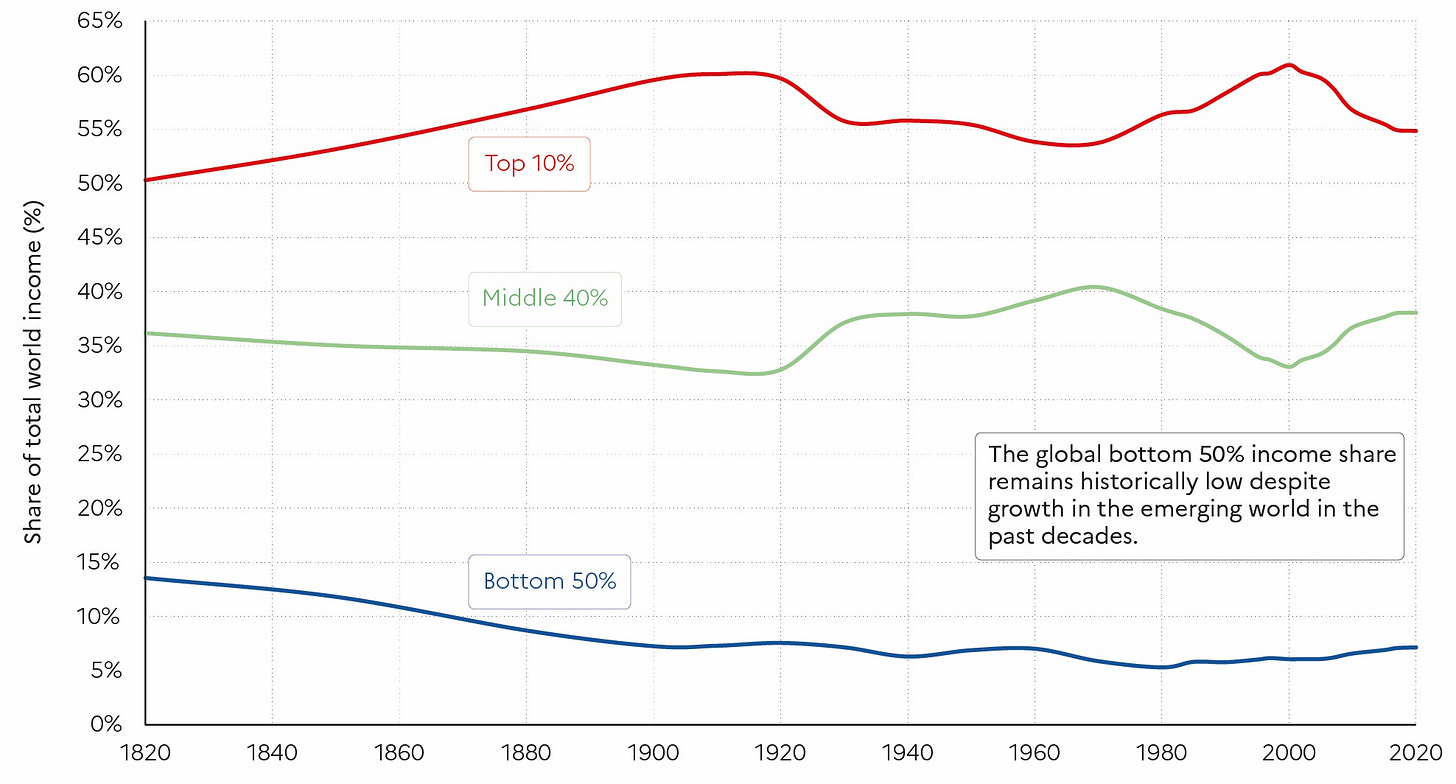

But even if we dodge the possible apocalypses and get to “radical abundance” there’s no guarantee that most of humanity will get to enjoy the benefits. As the graph at the top shows, humans don’t like sharing. The trouble is, we’re stuck with them until something better comes along.

"I’m not sure equality would make humans happy" I dislike having to agree with you, but you're probably right. Although many of us would like to think that we are in favor of equality, what we usually mean (whether we realize it or not) is "I want a share of their wealth," not "I'm happy to share my wealth with others."

In purely financial terms, the mean income worldwide is roughly $12,000. I don't think many of us in the US, Europe, or Australia would volunteer to reduce their income to that so that Afghans, Chadians, Haitians or the Congolese could enjoy a higher standard of living.

It occurs to me that longtermist thinking isn't entirely new. Medieval people believed their mind (or soul, rather, however that differs from the mind) would survive after death and go through a long period in purgatory followed by an infinite time in heaven. And that belief formed the basis of calculations about behaviour for many, the only difference being it was their own (or their soul's) longterm future they were concerned about rather than the longterm future of other (real, living) human beings.