Choices that matter

There's a simple lesson for interactive storytellers: people care about people more than they care about things

Early on in my game design career I got into writing choose-your-own-adventure style gamebooks. One of the gamebook series I created, Fabled Lands, is also the name of my company today, and the reason we named the company after it is that it was pretty revolutionary for its time. Each book added a new region to a huge fantasy world, and you could go back and forth between the books in an open-ended, sandbox narrative, making it a precursor in text form to things like Skyrim.

People nowadays think of gamebooks as rather old hat – and, after all, it was thirty years ago. In their heyday, though, gamebooks were a phenomenon, selling upwards of 100,000 units per title. And it's not as old hat as you might think: the same design skills I used in those days apply equally when I'm working on games today.

How do we get people to interact with a story? Well, in the first place that's completely the wrong question to ask. I could put a sudoku at the end of every chapter or episode and you'd have to solve it to progress through the story, but that doesn't address what would make people want to interact. What engages us about stories? What makes us care enough to get involved?

Here's a clue. One of my all-time favourite shows is Breaking Bad. I don’t care about crystal meth distribution in Albuquerque, or even that much about crime dramas. But I am fascinated by the problem of Walter White. Character – that’s what is compelling about great stories. When we put character and interactivity together we have the ingredients of relationship.

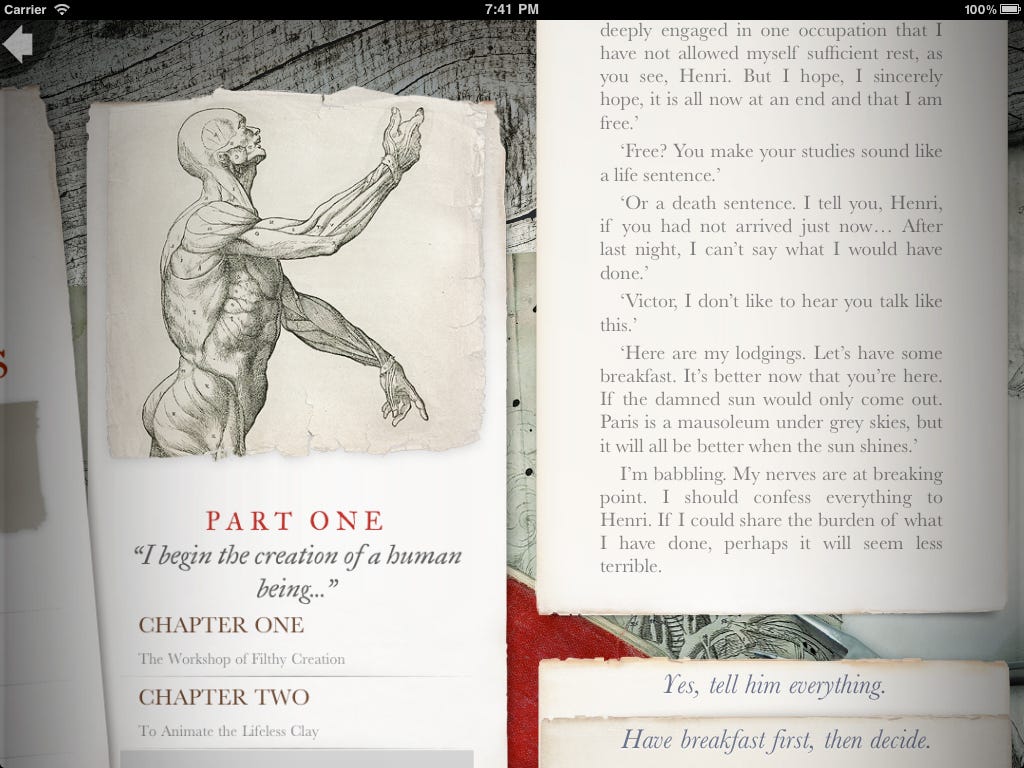

Relationship is at the heart of Frankenstein, an interactive take on Mary Shelley’s story that I wrote in 2012. You’re Victor Frankenstein’s confidante. He’s asking you for advice. Sometimes he'll take it, sometimes he won't. Sometimes he'll take it and then he'll blame you if things go wrong. And you get to shape the kind of person he becomes. When you first meet him in the story he’s a very young man, so the things you’re urging him to do will affect how he develops as a character.

Under the hood, Frankenstein is still a lot like a gamebook. The iPad is crunching the numbers for you, so there's no need to roll dice and keep notes. But the big difference is the variables being tracked aren’t combat ability and hit points. They’re things like trust, guilt, pride, and alienation – the elements that make up our relationship with Victor and his monster.

At the other end of the scale from Frankenstein, Dreams is a game I designed for Elixir Studios. The brief was, “like The Sims, but nothing like The Sims”. I admired The Sims as a game, but from a story viewpoint there are two glaring problems. First, your relationship with those characters is like bugs in a jar. There's no empathy. And secondly you’ve got this clunky, chemistry-set interface between you and the characters, with bars to show how tired or angry they are. It's all tell not show.

So in Dreams I swept that all away. You have the town, the characters, and you can reach in with a hand, tap them on the shoulder, and point out things or people you'd like them to interact with. Say I lead two characters to an art exhibit. If I listen in on them, I may hear them talking about the exhibit. They might bond or fall out over their opinions of it; that depends on their personality, tastes and mood. We had hundreds of unique lines of dialogue for each character, so they could do a whole lot of talking.

If you zoom right in on a character you get a one-on-one conversation. They tell you their hopes and fears. You might see a girl in the street, swoop down, and she'd say, "My boyfriend's gone to the art gallery with another woman. What are you going to do about it?" Whether I help her out or not, she'll remember. If I mess her life up, she'll bear a grudge and shake her fist every time she sees me.

In Dreams there's no layer between player and character. The interface is all in the world. One example: when they make friends or enemies, that generates magic dust that floats around the town. I can grab a pinch of that and sprinkle it to spice up the narrative. There are two flavours: dark dust for what I called "Tim Burton" effects, and the bright dust for "Walt Disney" effects.

When Telltale's Walking Dead game came out there was a lot of noise about that. Is it a good interactive story? Yes. The choices are intense, they're moral, they have far-reaching consequences, they're character-driven. But I can do all of that in text. So part of the reason book publishers were getting so excited about it, I think, is that they're being seduced by the beauty of realtime 3D graphics.

Images are immersive, there's no doubt about that. It's easier to believe in your pretend relationship with a character you can see on-screen than with a chunk of prose that only tells you what that character is doing or saying. But book publishers don't want to spend millions of dollars on game-quality graphics. What's the solution?

One option is comics. If you think comics just means The Beano or Superman, check out Mark Waid's talk at Tools of Change a decade ago. Comics don't have to be static, either. Japanese visual novels demonstrate that a minimal level of animation can bring comics-style graphics to life.

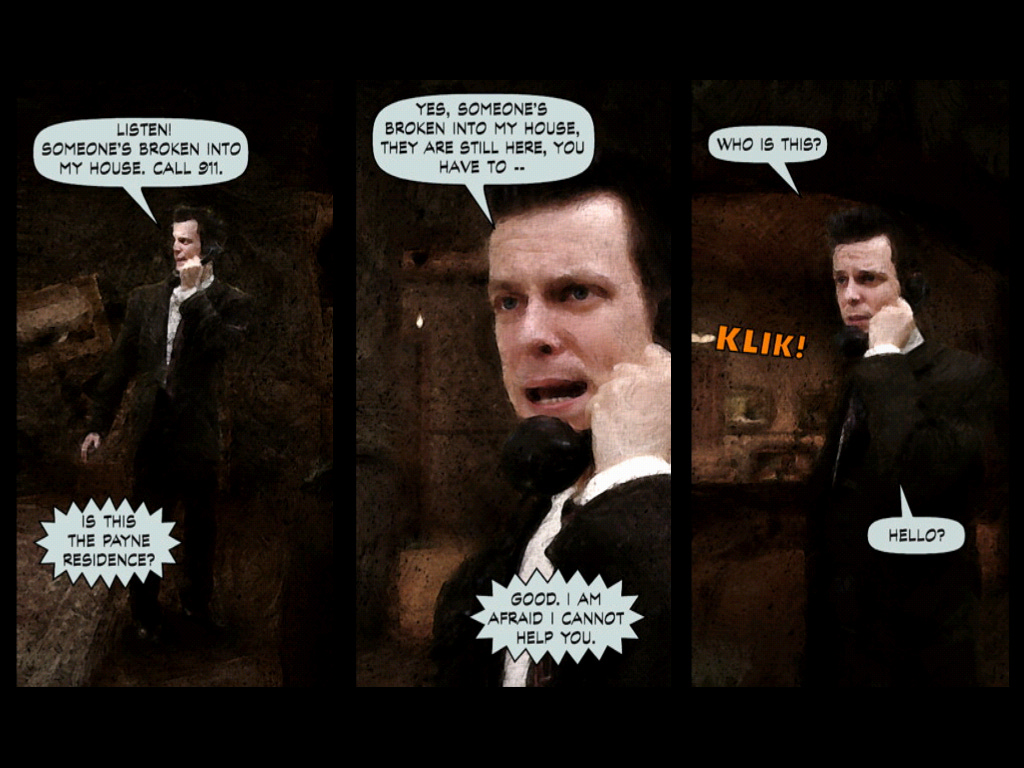

There's nothing new about using comics for a low-cost visual solution. Twenty years ago, Remedy didn't have the money for 3D cut scenes in Max Payne, so they gathered the development team, posed them for a photo-novel, and gave the final result a comic book touch-up. The result is classy, it fits the style of the story, and crucially, a decade on, it stands up against cut scenes from the time that would have cost ten times as much.

Another option is live action. It's cheaper than you'd think, especially when stylistically distressed – though of course you are limited in how far you can interact with it on a moment-by-moment basis. Alternatively, we could go the other way: simple and highly stylized, like Story Mechanics did with shadow-puppet visuals in The 39 Steps.

In short, there are lots of ways to get smart and stylish visuals into interactive stories without having to compete with videogame budgets.

What kind of relationships can we put in these stories? All kinds. Here's just one example. You're not James Bond, you're his controller at MI6. You're in touch with him all the time, giving him orders, but he's 007. He doesn't play well with others. So you have an adversarial relationship. And conflict, of course, is the motor of drama.

Really, though, we need to be going a lot further, breaking the whole frame of what historically constitutes a novel. How about: a massively multiplayer, ongoing, episodic, interactive soap opera? Here's the sort of thing Dickens would have done if he'd started out working at a game developer instead of a blacking factory. All the readers are able to interact around the fringes of the world and some of that feeds into the core narrative that everybody's following. It can even be text-based. The novel itself, in effect, is now the emergent main thread being woven out of an interactive world.

These are the kinds of experiments we should be doing. Novels, liberated from paper and cloth, don't need to remain in the form they've been constrained into for the last three centuries. Publishers will protest: "We're not in the videogames business." But you know what, that's fear talking. Those two land masses are connected now. There's going to be some evolving together, some exchange of creative DNA, some blurring of boundaries. A generation of authors have grown up playing games. Now it's time to mix those influences together and see what wholly new media we might create.

Postscript: You can hardly have failed to notice that most of the examples I cite here are from at least ten years ago. That’s because this is an updated version of a talk I gave at the Groucho Club back then. I’d like to say that everything changed in the interim, that interactive storytelling has been transformed so that what players are doing is interacting in ways that deepen their emotional involvement. Certainly that’s true in a few cases, but mostly games have just got better at movie-style writing. The emotional impact is being delivered in the cutscenes. It’s being delivered to the player, whereas it should instead be emergent from the player’s choices. Some game developers see that basic point, that people care more about people than they do about things. Character is what grabs us, plot is just a MacGuffin. So the key points of the talk are just as valid today.